At its most basic, tail is a program on writing into the UNIX command-line that shows the tail end of a text file. Let’s say that you wanted to see what is new on a log file for a system app, but you also wanted to avoid all of the old information as well. Well, there just happens to be a UNIX command-line utility that lets you do just that. Tail prints 10 lines of data from any file in the OS system and, at its most basic, a command using tail looks like the following: tail filename

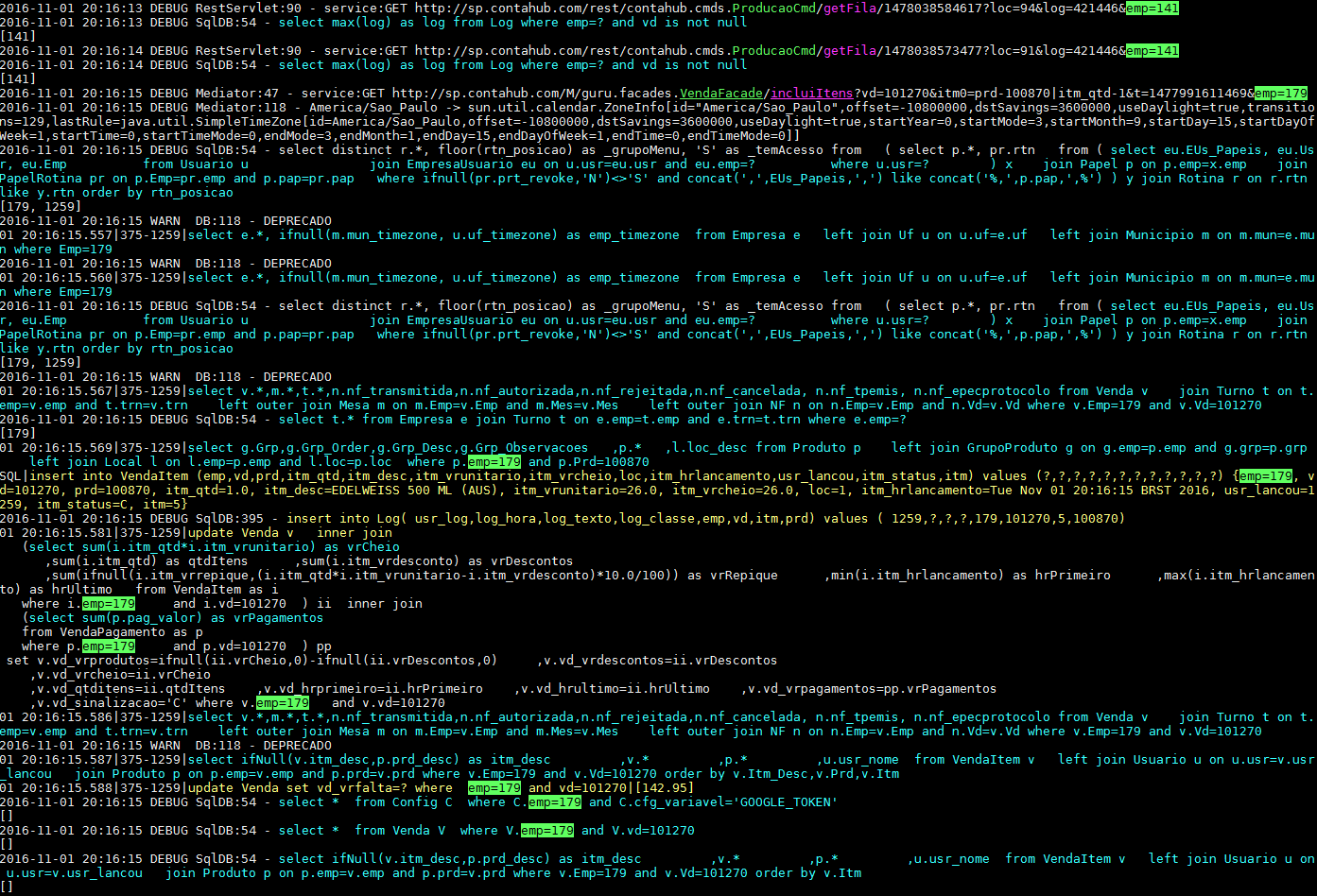

The program is most likely used by system administrators to monitor the growth of the log files and manages errors the occur within LINUX or UNIX operating systems, as it is common for application on such OS’s to record error messages to system log files. Specifically, the user may deploy the -f option to run tail for error checking, but, as you will see in the blog, you can use the tail command for much more.

LINUX is not UNIX

But before we dive into the true nation of the command line, the mysteries of tail, and how you can use it, it is important to make a few distinctions first.

Number one, UNIX was a proprietary system owned by AT&T and developed jointly with GE in the 60’s. In the 70’s, the 16-bit OS MINUX was developed based on UNIX and released for academic use, although the code remained copywrited. Then, in 1991, one site tells us, Linus Torvald released his free operating system kernel call LINUX under the free GNU license. But, while Torvald is credited with completing the actual LINUX kernel, many believe it would not have become an OS without the help of the GNU project, started in 1985 by Richard Stallman, according to Search Data Center.

After all, it takes free software to run on a free kernel to be called an OS as we know them, and so many believe that LINUX should be rewritten and GNU/LINUX. In any case, the upshot is that the system is free to use, free to manipulate, and free to share. Further, in order to distinguish their project from UNIX, Stallman used a recursive acronym as its name: a GNU (ga-noo) is also a wildebeest, but it also stands for GNU’s Not UNIX.

It is less clear how LINUX got its name, though some sources claim it too stands for a non-Unix declaration: LINUX Is Not Unix. And others’ claim it is Linus’ UNIX. Either way, both operating systems are intrinsically linked, much of which applies for tail on one is true for the other.

LINUX Heads and Tails

If you count yourself among those you are upright and facing the right way and pay any attention to the command-line then you have most likely heard of the cat program. While cat is certainly helpful for displaying file content when you have to pour over log file after log files sometimes you just want to see something specifically. Say, you just want to see that last 10 lines of a file, or the first 10… well, the LINUX command-line can do that. Rather than scrolling through page after page of log files, you can easily be taken right to the top of the files or the end using the head or tail LINUX command.

Say you want to see a list of usernames and passwords. Well, thanks to our friends at TecMint, the head LINUX command would look something like this:

head [options] [file(s)] or # head /etc/passwd

The same, then, would be true for the tail LINUX command:

# tail /etc/passwd

Further, it is easy to augment the number of lines printed from the command-line by using the n argument:

?# tail -n 3 /etc/passwd

Moreover, arguments/options life -f (follow) and -s(sleep) can be used to monitor an open log file while it is being written and break off that file at a specified time. These two arguments should always be used together, but don’t worry if you forget. Control-C will always break and unresponsive command.

Plus combining commands is quick and easy, as tail LINUX can be “piped” to other commands, such as illustrated by the following example, which shows the ls command being linked with the tail command to limit the results to five:

ls -t /etc | tail -n 5

The LINUX Mascot is a Penguin

As the story goes, Linus Torvalds announced in 1996 that a penguin would be the official mascot of LINUX. He relayed an allegorical story about being bit by a penguin while in Australia, and the idea stuck. The mascot was aptly named Tux, another variation on the LINUX is not UNIX, namely Torvald’s UNIX.

Now, the reason this is worth mentioning is that up until now, LINUX was kind of an underground, geeky operating system for coders and those who liked to get their hands dirty with code. Tux was really LINUX’s introduction to the world, and it wasn’t long before the world took notice of this flashy, free operating system for your PC.

And since the code was free to use, free to augment, and free to share, it meant that enterprising software companies could take it, change it, and start charging money for their own version of it. Soon, LINUX would be developed and made proprietary by SUSE-LINUX, Red Hat LINUX, STEAM OS, and Microsoft. Yes, Microsoft.

Without diving too deep into it, Microsoft needed the LINUX command line and its built-in security to roll out its new brand of Sphere OS. This OS will go into many items that were previously not thought of as being smart devices, like, say, your toaster. With the new Microsoft OS, you can now update and automate that device.

And, thanks to LINUX and Microsoft, you might now be able to program your fridge from your laptop. But, you have got to start somewhere, and using the tail LINUX command to view the status of a log folder is a good place to start. Note: it is helpful to use the sudo command when looking at system files because some may be locked, as is shown below:

sudo tail /var/log/boot.log

Tail LINUX Specifics and Examples

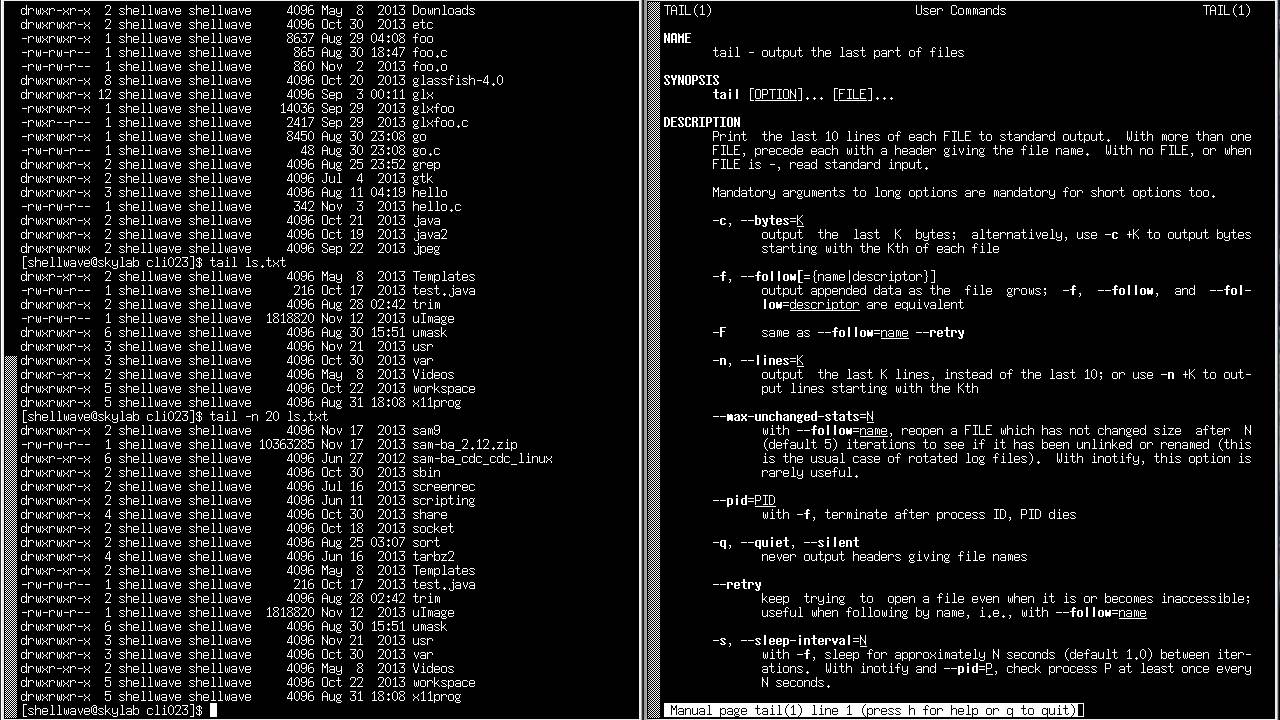

But maybe you wanted to see the last 20 entries of the boot log file, so your command would look something like this: tail -n20 <filename>. But perhaps you want to go 30 lines down in a file and start parsing there. Then your command could look something like the following: tail -n+20 <filename>.

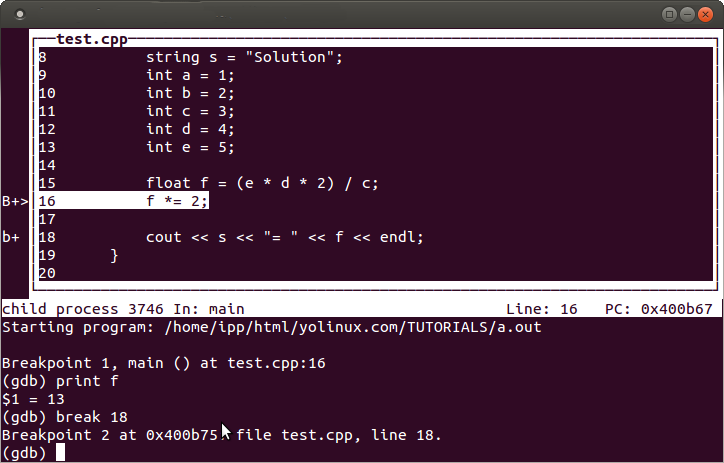

Of course, you could also output bytes in favor of lines, as suggested by this blog, by using the c switch, and that would look similar to this line: tail -c20 <filename>. And monitoring a file is simple, too, with the f argument. Common reasons for wanting to see an app while it is running is to check for errors, so you can use a tail command to check the file at certain intervals using the following command: tail -F -s20 <filename>. If for some reason, the file is inaccessible, you can command the tail to keep checking until it becomes available, using an argument the looks like the following: sudo tail --retry -F <filename>. Or maybe you wanted to use the tail to monitor a process through logs until it ends. Well, tail can do that too.

These are some of the more common uses for the UNIX and LINUX command tail. It is important to note that the use of sudo is only necessary if you need elevator permissions to open files. It is generally not necessary, but if you encounter a file that denies you permission it may come in handy.

Tail LINUX Wrap-up

For more info on the tail command, why not broaden you LINUX command-line skills be typing in the using a command like the following: man tail. The man command is short for manual, and it can be used to find out more about any command.

Remember, the tail command reads the last 10 lines of any text files and writes the results to standard output (the monitor screen). Hopefully, now you understand a little bit better how this command works on its own, with other processes, and in combination with switches as well. You can also use the –pid (program ID) and -f switch to monitor the program’s file and kill the tail command when the program ends. See if you can figure out what that might look like, and keep practicing with tail LINUX.